Diversity: The Ethical Choice

Posted: September 26, 2011 | Author: rjrock | Filed under: Sociology | Tags: corporations, democracy, discrimination, diversity, equality, legitimizing myths, semantic framing, social dominance theory | Leave a commentThe United States is one of the most diverse nations on the earth, originally conceived so, and often described as a great melting pot, as “all nations are melted into a new race of man, whose labours and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world” (St. John de Crèvecoeur, 1782). Yet, despite the country’s diverse population, the workplace remains a place of inequality as women and minorities continue to earn less than their white male counterparts (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011; U.S. Census Bureau, 2009) and advance less in managerial and professional positions (Kinicki & Kreitner, 2008). The question of workplace diversity is a polarizing debate with proponents of diversity measures arguing the business benefit of diversity (Herring, 2009) and opponents arguing that diversity programs are a form of reverse discrimination (Kinicki & Kreitner, 2008). To what degree should employers, in either government or business, seek to promote diversity and encourage equality and what are the ethical considerations of such a position? Both the government and business employers are powerful entities that can continue to enhance the dominant position of white males, or attenuate the existing dominant hierarchy by increasing diversity and working to break the glass ceiling. Given both types of institutions are granted their power by civil society, a society that is increasingly made up of minorities (Kinicki & Kreitner, 2008), it is a societal obligation, the ethical choice, and good business, to increase diversity, address equality issues in the workplace, and turn the American melting pot myth into reality.

Employers are powerful institutions that are responsible for allocation of resources like salary, benefits, bonuses, and company stocks, based on employee role, span of control, and contribution to the organization. While equal rights and equal pay legislation made it illegal to discriminate “based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin“ (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2011b, p. 1), the number of workplace discrimination cases continue to rise and cost employers more than $319 million in 2010, not counting litigation costs (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2011a). Many employers invest in extensive human resource organizations that have a sophisticated grasp on the implications of equal rights legislation on organizations; and they employ professionals, like I/O psychologists and attorneys, to establish fair policies and employment practices, and decrease litigation risk to an organization (Aamodt, 2010). In fact, employers often perform statistical analysis of employment practices to understand whether the practice could have an adverse impact against members of a protected class. For example, testing is a practice employers use for employee selection in the hiring process; even when an employment test is determined to be reliable, valid, and cost-efficient, care is taken to assure testing predicts performance equally well for all applications (Aamodt, 2010). Because governments and corporations have a fiduciary duty to citizens and shareholders, employers should continue to care about the issue of adverse impact, but more importantly, both government and corporations have a civil responsibility to treat members of society fairly, because societal institutions derive their legitimacy from the consent of civil society (Castello ́ & Lozano, 2011; United States, 1776). In light of the growing minority population, pervasive inequality in the workplace, and the origin of organizational legitimacy, it is an ethical responsibility for employers to increase diversity, but how far should employers go? More importantly, what specifically should employers do to increase diversity?

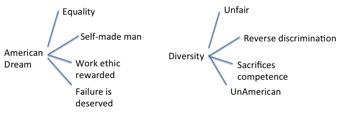

Determining the extent employment practices should be adjusted, to increase diversity is challenging without a theoretical perspective that identifies the basic constructs that maintain inequality. In Social Dominance, Sidanius and Pratto (1999) argue that in societies with an economic surplus, dominant hierarchies are formed that maintain control over distribution of resources in a complex interplay between institutions and individuals, coordinated through legitimizing myths that justify unequal distribution of resources. In order to attenuate the effects of dominant hierarchy-enhancing institutions on subordinate minority groups, legitimizing myths need to be understood and reframed. An important legitimizing myth in the immigration debate is the notion of the United States as a meritocracy, also know as the American Dream, where “individuals can control their economic well-being and are responsible for their economic success or failure” (Fiske-Rusciano, 2009, p. 343), despite their differences.

Figure 1 highlights the relationship between the semantic frames of the American Dream and the diversity debate, with common challenges to diversity (Morrison, 1992), structurally related to the legitimizing myth of the American Dream. In order for employers to gain acceptance for diversity programs, diversity needs a new semantic frame inside an organization, that of diversity as fair, ethical, beneficial, and distinctly American. The new semantic frame requires organizational support that includes practices that promote accountability, and the recruitment and development of members of protected classes into leadership positions (Kinicki & Kreitner, 2008). Instead of simply addressing the risk of adverse impact, leaders, human resource professionals, and I/O psychologists should take a proactive role in developing practices that promote diversity.

In fact, I/O psychologists have a greater ethical responsibility and greater opportunity than most because of their status as professionals and their deep knowledge of the subject. Lefkowitz (2003) addresses the ethical responsibility arguing that I/O psychologists expertise must benefit all of society rather than simply the clients that pay for their expertise. The opportunity for I/O psychologists is threefold, to promote fair testing and evaluation practices, to promote development and recruitment practices that increase diversity, and to challenge discriminatory practices. Testing and evaluation practices should do more than simply promote decision-making flexibility, rather they should be part of a comprehensive assessment practice that consider the benefits of organizational diversity, going beyond the narrow view of test scores. I/O psychologists should play a central role in promoting diversity by building development and recruiting practices that support diversity goals. Finally, when faced with discriminatory practices that represent an ethical dilemma, I/O psychologists are required to attempt to resolve the ethical conflict in accordance with APA guidelines (American Psychological Association, 2010); should discriminatory practices go unresolved, I/O psychologists should seek employment elsewhere, because failure to act is abrogation of responsibility to the society that grants I/O psychologists professional status.

In conclusion, the United States is at a crossroads, where minorities will soon be in the majority and the country needs to rethink the legitimizing myths that support the continued domination of women and minorities by the white male majority. As hierarchy-enhancing institutions, employers are in a unique position to embrace diversity programs, not only because they make good business sense, but also because embracing diversity is a sound ethical choice. However, embracing diversity will not be easy, not only because the existing legal framework enhances the existing dominant-hierarchy, but also because organizations will need to move away from the adverse impact thought processes of the past and towards the positive impact thought processes of the future. I/O psychologists that value a diverse perspective are poised as thought leaders in the coming future. Most importantly, it is time to change the semantic frame outlining the diversity debate from the American Dream back to the melting pot, and in so doing focus the dialogue on the positive impact of diversity on our nation, and the great changes we can create in the world.

References

Aamodt, M. G. (2010). Industrial/organizational psychology : an applied approach (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

American Psychological Association. (2010). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct: 2010 Amendments. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct Retrieved September 25, 2011, from http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx

Castello ́, I., & Lozano, J. M. (2011). Searching for new forms of legitimacy through corporate responsibility rhetoric. Journal of Business Ethics, 100(1), 1-19. doi: DOI 10.1007/s10551-011-0770-8

Fiske-Rusciano, R. (2009). Experiencing race, class, and gender in the United States (5th ed.). Boston, Mass.: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Herring, C. (2009). Does diversity pay?: Race, gender, and the business case for diversity. American Sociological Review, 74(2), 208-224.

Kinicki, A., & Kreitner, R. (2008). Organizational behavior : key concepts, skills & best practices (3rd ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Lefkowitz, J. (2003). Ethics and values in industrial-organizational psychology. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Morrison, A. M. (1992). The new leaders : guidelines on leadership diversity in America (1st ed.). San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey-Bass.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance : an intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression (Vol. x, 403 p.). Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

St. John de Crèvecoeur, J. H. (1782). Letters from an American farmer; describing certain provincial situations, manners, and customs, not generally known; and conveying some idea of the late and present interior circumstances of the British colonies in North America. Dublin,: Printed by John Exshaw.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2011). Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by detailed occupation and sex. In cpsaat39.pdf (Ed.). Washington DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2009). Table HINC-05. Percent Distribution of Households, by Selected Characteristics Within Income Quintile and Top 5 Percent in 2009. In new05_000.htm (Ed.). Washington DC: U.S Census Bureau.

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2011a). Enforcement & Litigation Statistics: All Statutes FY1997 – FY2010 Retrieved September 25, 2011, from http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/all.cfm

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2011b). Federal Laws Preventing Job Discrimination: Questions and Answers Retrieved July 23, 2011, from http://www.eeoc.gov/facts/qanda.html

United States. (1776). In Congress, July 4, 1776, a declaration by the representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled. Philadelphia: Printed by John Dunlap.

Social Dominance Theory: The U.S. Minority Experience

Posted: September 4, 2011 | Author: rjrock | Filed under: Sociology | Tags: african american experience, ALMA, Alma Award, ethnic relations, Ethnic studies, hispanic experience, Hispanics, Immigration Reform, latino experience, LGBT, liminal legality, marxist school, National Council of La Raza, NCLR, oppression, race relations, Racism, social dominance theory | 1 CommentThe United States is often viewed as a classless society (Fiske-Rusciano, 2009), where everyone has an equal opportunity to be successful and yet, despite significant legislation intended to provide equal rights and opportunities, there continue to be disturbing disparities that are suggestive of systematic problems that prevent equal participatation in U.S. society by minorities. African-Americans and Hispanics have less wealth than whites (Kochhar, Fry, & Taylor, 2011), earn less income than whites (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009), have lower rates of participation in higher education (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011), and have unequal representation in the U.S. Congress (U.S. Congress & Manning, 2011). In the 19th century, De Tocqueville (1839), described his observations of U.S. democracy, concerned over the “tyranny of the majority” or the ability of the majority to hold unequal power over the minority. While De Tocqueville was not explicitly worried over ethnic or racial minorities, the observations appear nonetheless prophetic. The white majority has dominated nearly every aspect of social life in the United States since the country’s inception, holding economic, political, legislative, and religious power (Zinn, 2003). In addition, white majority perspectives have dominated U.S. cultural life including language, art, media, and history (Zinn, 2003). It is plausible to believe that minorities, have long been in a subordinate relationship to the dominant white society in the United States, and are members of a near-permanent underclass enforced by white institutions and individuals, to maintain their dominant social status, and justify unequal distribution of resources.

Social Dominance Theory

Social Dominance Theory is the lens through which the experiences of African- Americans and Hispanics will be examined in this paper, and as such; require a brief review of its major tenets. Developed by Pratto and Sidanius (1999), Social Dominance Theory (SDT) describes the observation that all human societies with a resource surplus are structured as group- based social hierarchies with dominant and subordinate groups, whereby the dominant groups control access to resources; a condition the authors consider universal to humanity. Pratto and Sidanius (1999) argue that the common structure for the group hierarchy is trimorphic and based on three distinct systems that include an age system, gender system, and an arbitrary-set system that can be class, race, ethnicity, religion, origin, or otherwise, and that the group structures are created from the combined effects of discrimination from individuals, institutions, and intergroup processes. The coordination of discrimination occurs across individuals and institutions, through the notion of legitimizing myths; the ideas or values that are shared between dominants and subordinates alike (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). SDT is a valuable lens through which to examine minority experiences, using race and ethnicity as the arbitrary-set systems, in the hopes of shedding light on the ways in which individual and institutional discrimination combine with legitimizing myths to maintain inequality in the U.S.

SDT and the African-American Experience

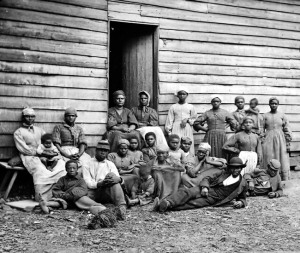

from the earliest arrival of African slaves to America’s shores in 1619, the African- American experience in the United States has been one of subjugation and subordination (Zinn, 2003). During slavery, a common legitimizing myth of the time was “the argument that slavery was actually benevolent and in the interest of Blacks because they were simply incapable of attending to their own affairs suggesting that slavery was not only economically advantageous but morally compelling (Zanna & Olson, 1994, p. 309)”. Whereas the combined effect of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Union victory should have begun a new era of freedom for slaves, instead, whites continued to dominate African-Americans using institutions besides slavery. Laws took away African-American voting rights, like poll taxes, property qualifications, and literacy tests (Zinn, 2003); additionally, there were Jim Crow segregationist laws and practices that “extended overt racism against African-Americans into the middle of the twentieth century (Fiske-Rusciano, 2009, p. 173)”.

The birth of the twentieth century saw African-Americans continue to be subordinate to the white dominant class (Zinn, 2003). In the period between the 1870s and 1940s, religious institutions in the South were segregated and “the southern religious community often gave aid and comfort to the forces that adopted disenfranchisement, legal segregation, and proscription (Hill, Lippy, & Wilson, 2005, p. 715)”. The segregation of churches served to create exclusively African-American churches that developed into socially distinct institutions of African-American faith and served as rallying points for social justice (Hill, et al., 2005). African-American churches are an example of what Pratto and Sidanius (1999) would call a hierarchy-attenuating institution, or an institution that works to moderate the influence of institutions that enhance inequality, like a white dominated justice system, white schools, or white religious institutions. Other hierarchy-attenuating institutions that took form in the early twentieth century include the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and later, during the Civil Rights movement, equally transformative organizations formed, supporting social justice for African- Americans, like the Congress of Racial Equality, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the Southern Poverty Law Center (Zinn, 2010). The civil rights era saw rapid change beginning with the landmark case, Brown vs. the Board of Education, which “held that segregated schools were inherently unequal because of the message that segregation conveyed: that African-American children were an untouchable cast, unfit to go to school with white children (Lawrence, 1990, p. 446)”. The era culminated in the latter half of the sixties with the Civil Rights Act of 1965, a series violent racial conflagrations in cities across the United States in 1967 that pitted white police officers against African-Americans, and the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (Zinn, 2010). These examples of from the civil rights movement serve to illuminate the SDT concept of a collaborative intergroup processes, or process shared by dominants and subordinates alike, that are supported by legitimizing myths (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). The riots can be considered self-debilitating behavior given they affected primarily African-American neighborhoods, while the behavior may have reinforced the bias of white police officers, suggestive of a collaborative intergroup process that reinforces the existing hierarchy.

While the end of the Civil Rights era saw significant changes in legislation ending years of overt discrimination, as we take stock over forty years later, we find that institutionalized discrimination still exists. In The 2000 Presidential Election in Black and White, Rusciano (2008) notes that votes in largely black districts were invalidated at a higher rate than those in largely white districts, likely because of dilapidated voting machines in poorer black neighborhoods. Campbell (1984) describes in To Be Black Gifted and Alone, the plight of a successful black women attempting to deal with the pressure and resentment of living a liminal existence, not at home with former friends that occupy a different social class, while equally not at home with white colleagues.

While the end of the Civil Rights era saw significant changes in legislation ending years of overt discrimination, as we take stock over forty years later, we find that institutionalized discrimination still exists. In The 2000 Presidential Election in Black and White, Rusciano (2008) notes that votes in largely black districts were invalidated at a higher rate than those in largely white districts, likely because of dilapidated voting machines in poorer black neighborhoods. Campbell (1984) describes in To Be Black Gifted and Alone, the plight of a successful black women attempting to deal with the pressure and resentment of living a liminal existence, not at home with former friends that occupy a different social class, while equally not at home with white colleagues.

Of course, the numbers speak for themselves, the 2010 Census indicate that African- Americans make up 12.6% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010), and yet only make up 1.5% of the total number of households in the top income quintile and nearly 33% of the bottom 20% income quintile (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). In addition, the African-American unemployment rate in the United States remains twice the rate of their dominants white counterparts (U.S. Department of Labor, 2011). In spite of legislation guaranteeing equal rights under the law, African-Americans have yet to attain anything resembling full equality, as measured by access to positive social value, “or desirable material and symbolic resources such as political power, wealth, protection by force, plentiful and desirable food, and access to good housing, health care, leisure, and education” (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999, p. 272). Rather, African- Americans continue to have a disproportionate share of negative social value, things like underemployment, disproportionate punishment, stigmatization, and vilification.  For example, the U.S. Department of Justice statistics demonstrate the disproportionate African-American share of capital punishment, making up 41.5% of prisoners on death row in the United States (U.S. Department of Justice & Snell, 2010).

For example, the U.S. Department of Justice statistics demonstrate the disproportionate African-American share of capital punishment, making up 41.5% of prisoners on death row in the United States (U.S. Department of Justice & Snell, 2010).

To conclude the view of the African-American experience in the United States, African- Americans continue to have a lower share of resources representing positive social value and a significantly higher share of resources representing lower social value. Inequality likely continues because of the combined effect of individual discrimination, institutional discrimination, and collaborative intergroup processes that maintain the existing hierarchy.

SDT and the Hispanic Experience

As established in the introduction, people of Hispanic origin in the United States suffer from many of the same socioeconomic disparities as African-Americans, with unequal access to wealth, income, and power. For purposes of contrast, the Hispanic experience will be reviewed with a focus on the violence of arbitrary-set systems, the role of hierarchy-enhancing legitimizing myths in the continue subordination of Hispanics in the United States, and an examination of hierarchy-enhancing and hierarchy-attenuating cultural institutions that allow the exploration of the impact of white culture on the minority experience.

In the debate over Hispanic immigration to the United States, many Americans appear to lose sight of the historical context of the Hispanic experience in the United States, particularly that of Mexican-American Hispanics whose families have geographical roots that predate their lands annexation by the United States. In the early 1800s, Mexico was a large country that won independence from Spain, whose national territory included what today is Mexico, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Utah and parts of Colorado (Zinn, 2003). Half of Mexico was taken by force following the successful U.S. invasion of Mexico, the same war that ironically sparked Henry David Thoreau’s act of civil disobedience that later became one of the seminal works outlining the duty of citizens to resist unjust civil government (Zinn, 2003). The invasion of Mexico was a violent and aggressive act that included not only the violent subjugation of the Mexican people, but widespread violence, theft, and rape of the civilian population.

Reviewing the conquest of Mexico in light of SDT, one observes the interplay between gender systems and arbitrary-set systems described by Pratto and Sidanius (1999), who note that only in arbitrary-set systems is the extreme type of violence described by Zinn (2003) found. Pratto et al., (2006) describe the lethality of arbitrary-set system violence:

Arbitrary-sets are the only type of system in which total annihilation is found. That is, there are cases in which one clan or race or ethnic group has exterminated another. There are no known cases in which adults killed all the children, or men killed all the women, in a society. Finally, while by definition, the age system is focused on the control of children by adults, and the gender system is focused on men’s control of women, social dominance theory argues that arbitrary-set hierarchy primarily focuses on the control of subordinate males by coalitions of dominant males. This, in fact, is a primary reason that arbitrary-set hierarchy is associated with extraordinary levels of violence. (p. 274)

While the rape of Mexican women and girls might appear to be gender system domination, SDT concludes that rape is used primarily as a tool of arbitrary-set system violence to further enhance subordination (Pratto, et al., 2006). While the conquest was Mexico was a violent affair, there was a significant debate in the United States on the righteousness of the war, with Americans on both sides of the debate. Proponents of the war argued primarily for the legitimizing myth of “manifest destiny” and to save the Mexican people from their vices (Zinn, 2003). According to Zinn (2003), one newspaper, the Congressional Globe, wrote, “we must march from ocean to ocean…It is the destiny of the white race, it is the destiny of the Anglo-Saxon race (p. 171)”. So there is considerable irony in the modern immigration debate, given the historical context for the U.S. relationship with Mexicans, began as one of territorial conquest, and racism as a pretext for social domination.

As we consider the modern immigration debate in terms of the hierarchy-enhancing legitimizing myths that frame the debate, there are several related myths. The first myth to address is the notion that immigrants are responsible for U.S. economic problems. The Federation on American Immigration Reform, a special interest group with racist origins (The Pioneer Fund, 2011; Zeskind, 2005), frame the myth by distributing reports that suggest illegal immigrants that cross the border from Mexico are tax-evaders, heavy users of social services, have high rates of criminality, and take American jobs (FAIR, 2010), costing U.S. taxpayers $113 billion dollars annually (Martin & Ruark, 2010) Unbiased reports and peer reviewed research tell a different tale, suggesting that illegal immigration is an economic wash, neither helping nor hurting the economy (Hanson, 2007) and that illegal immigrants actually pay significant social security taxes whose benefit they can never claim, roughly $500B in 2005 (O’Carroll, 2006). Reports of higher incarceration rates are true, but that does not necessarily mean that Hispanic illegal immigrants engage in higher rates of criminal activity, because institutional discrimination in the justice system accounts for higher incarceration rates as subordinates absorb a higher share of negative social value. One study found, that after adjusting for institutional bias, Hispanic illegal immigrants had lower rates of criminal activity and surmised that questionable legal status was a contributing factor (Hagan & Palloni, 1999). Despite significant evidence to the contrary, the hierarchy-enhancing legitimizing myth that Hispanic illegal immigrants are the cause of U.S. economic problems, serves to allow dominant institutions, namely the U.S. government, to attempt to legislate discriminatory immigration policies that maintain the dominant hierarchy. For those that believe that a discriminatory immigration policy is unlikely to pass, a quick review of the last one hundred years tells a very different story, as both the Mexican “Repatriation” Campaign and “Operation Wetback” were the result of hierarchy-enhancing immigration policies that forcibly deported millions of Mexicans, many of them U.S. citizens (U.S. Commission On Civil Rights, 1980). Those policies had as much to do with immigration as does the immigration debate today, meaning the debate simply continues the tradition of social domination that began with the conquest of Mexico.

As we consider the modern immigration debate in terms of the hierarchy-enhancing legitimizing myths that frame the debate, there are several related myths. The first myth to address is the notion that immigrants are responsible for U.S. economic problems. The Federation on American Immigration Reform, a special interest group with racist origins (The Pioneer Fund, 2011; Zeskind, 2005), frame the myth by distributing reports that suggest illegal immigrants that cross the border from Mexico are tax-evaders, heavy users of social services, have high rates of criminality, and take American jobs (FAIR, 2010), costing U.S. taxpayers $113 billion dollars annually (Martin & Ruark, 2010) Unbiased reports and peer reviewed research tell a different tale, suggesting that illegal immigration is an economic wash, neither helping nor hurting the economy (Hanson, 2007) and that illegal immigrants actually pay significant social security taxes whose benefit they can never claim, roughly $500B in 2005 (O’Carroll, 2006). Reports of higher incarceration rates are true, but that does not necessarily mean that Hispanic illegal immigrants engage in higher rates of criminal activity, because institutional discrimination in the justice system accounts for higher incarceration rates as subordinates absorb a higher share of negative social value. One study found, that after adjusting for institutional bias, Hispanic illegal immigrants had lower rates of criminal activity and surmised that questionable legal status was a contributing factor (Hagan & Palloni, 1999). Despite significant evidence to the contrary, the hierarchy-enhancing legitimizing myth that Hispanic illegal immigrants are the cause of U.S. economic problems, serves to allow dominant institutions, namely the U.S. government, to attempt to legislate discriminatory immigration policies that maintain the dominant hierarchy. For those that believe that a discriminatory immigration policy is unlikely to pass, a quick review of the last one hundred years tells a very different story, as both the Mexican “Repatriation” Campaign and “Operation Wetback” were the result of hierarchy-enhancing immigration policies that forcibly deported millions of Mexicans, many of them U.S. citizens (U.S. Commission On Civil Rights, 1980). Those policies had as much to do with immigration as does the immigration debate today, meaning the debate simply continues the tradition of social domination that began with the conquest of Mexico.

Media portrayals of Hispanics are another element of how cultural institutions support discrimination. The National Association of Hispanic Journalists for many years published the Network Brownout Report, studying Latino portrayal in the national media (Montalvo & Torres, 2006). The report demonstrates the role of the media as a hierarchy-enhancing institution, with nearly 30% of images analyzed depicting negative images of Latinos, where “images of day laborers standing in a parking lot or immigrants crossing the border often provide viewers with a negative, menacing and stereotypical depiction of Latinos (Montalvo & Torres, 2006, p. 13)”. While white dominated media institutions use legitimizing myths and stereotypes to enhance the existing hierarchy, Latino social justice organizations work to moderate the impact of mainstream media by providing an altogether different view.

The National Council of La Raza (NCLR) is a Latino social justice organization born out of the civil rights movement that seeks to combat discrimination and advocate for Latino rights, using media to educate the Latino community, challenge discriminatory stereotypes, and help the community take action (Rock, 2011). NCLR challenges stereotypes by providing alternative views in the mainstream media and through social media, using public service announcements and the NCLR ALMA Awards, a nationally televised awards show similar to the Oscars, but with a distinct focus on Latino entertainers, to promote “fair, accurate, and representative portrayals of Latinos in entertainment (Murgia, 2011, p. 1)”. NCLR, a hierarchy-attenuating organization, attempts to use media to provide a dramatically different media portrayal of Latinos in order to attenuate the effects of the dominant hierarchy.

The National Council of La Raza (NCLR) is a Latino social justice organization born out of the civil rights movement that seeks to combat discrimination and advocate for Latino rights, using media to educate the Latino community, challenge discriminatory stereotypes, and help the community take action (Rock, 2011). NCLR challenges stereotypes by providing alternative views in the mainstream media and through social media, using public service announcements and the NCLR ALMA Awards, a nationally televised awards show similar to the Oscars, but with a distinct focus on Latino entertainers, to promote “fair, accurate, and representative portrayals of Latinos in entertainment (Murgia, 2011, p. 1)”. NCLR, a hierarchy-attenuating organization, attempts to use media to provide a dramatically different media portrayal of Latinos in order to attenuate the effects of the dominant hierarchy.

The Hispanic experience illuminates how the extreme violence possible within arbitrary- set systems male groups, created dominant hierarchies allowing the dominant group to control resources, like territory, and subordinate other male-groups. In addition, the Hispanic experience has allowed a view into how the legitimizing myths described in SDT have had a significant impact on Hispanics through their use in promoting both war and discriminatory laws to justify the maintenance of the existing hierarchy. Finally, it is possible to view the current immigration debate and understand the role that both hierarchy-enhancing and hierarchy-attenuating institutions play in framing both dominant and subordinate views of the legitimizing myths that surround the debate.

Conclusion

Our national and social history, viewed from two very different perspectives, tells two very different stories. The U.S. remains dominated by whites controlling the institutions of power that define our cultural and historical context, therefore, our history is replete with legitimizing myths that justify the behaviors, both noble and heinous, that led the U.S to this place in history. American exceptionalism, Manifest Destiny, the United States as a beacon, and the American Dream, are powerful stories through which current and past events are framed. From the viewpoint of subordinate groups, America’s legitimizing myths are debilitating, and create a situation where both dominants and subordinates act in concert to maintain white domination over institutions, wealth, income, and items of positive social value.

Individuals in the subordinate group can achieve success in the United States, however, there are often consequences for subordinates that access resources of positive social value, such as in the story mentioned earlier by Campbell (1984), about Leanita McLain, a successful black journalist. McLain could not handle the pressures of deviating from the existing gender-set and arbitrary-set systems, as social forces from both dominant and subordinate institutions and individuals became too much to handle, so rather than continue to existing in the space between dominants and subordinates, she took her own life (Campbell, 1984).

Social Dominance Theory is useful to understand the complex interplay of forces, both institutional and individual, that combine to preserve existing hierarchies. This theory allows sociologists and historians to examine the past and present, not through the lens of either dominants or subordinates, but rather, to take a step back and examine our past and present using the holistic viewpoint of our shared humanity, and perhaps in doing so, inform a better future where resources are shared more equally.

References

Campbell, B. M. (1984). To be Black, Gifted, and Alone. In R. Fiske-Rusciano (Ed.), Experiencing race, class, and gender in the United States (5th ed., pp. 175-179). Boston, Mass.: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

FAIR. (2010). Federation for American immigration reform 2010 annual report (pp. 32). Washington DC.

Fiske-Rusciano, R. (2009). Experiencing race, class, and gender in the United States (5th ed.). Boston, Mass.: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Hagan, J., & Palloni, A. (1999). Sociological criminology and the mythology of Hispanic immigration and crime. Social Problems, 46(4), 617-632.

Hanson, G. H. (2007). The economic logic of illegal immigration. Council on Foreign Relations, 26(April 2007), 1-52.

Hill, S. S., Lippy, C. H., & Wilson, C. R. (2005). Encyclopedia of religion in the South (2nd ed.). Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press.

Kochhar, R., Fry, R., & Taylor, P. (2011). Wealth Gaps Rise to Record Highs Between Whites, Blacks, Hispanics Pew Social & Demographic Trends. Washington DC: Pew Research Center.

Lawrence, C. R., III. (1990). Acknowledging the Victims’ Cry. In R. Fiske-Rusciano (Ed.), Experiencing race, class, and gender in the United States (5th ed., pp. 446-448). Boston, Mass.: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Martin, J., & Ruark, E. (2010). The fiscal burden of illegal immigration on United States taxpayers (pp. 1-95). Washington DC: Federation for American Immigration Reform.

Montalvo, D., & Torres, J. (2006). 2006 network brownout report: The portrayal of Latinos and Latino issues on network television news, 2005. In N. A. o. H. Journalists (Ed.), Network Brownout Report (pp. 1-24). Washington DC: National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

Murgia, J. (2011). ALMA Awards 2011 Retrieved August 26, 2011, 2011, from http://www.almaawards2011.com/about_the_alma_awards.html

O’Carroll, P., Jr. (2006). Statement for the record: Administrative challenges facing the Social Security Administration. Washington DC: U.S. Senate

Committee on Finance Retrieved from http://www.ssa.gov/oig/communications/testimony_speeches/03142006testimony.htm.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. (2006). Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. European Review of Social Psychology, 17, 271-320. doi: 10.1080/10463280601055772

Rock, R. (2011, September 1, 2011). Social Media, Social Change: How the National Council of La Raza Uses Social Media to Advance Latino Issue. journey24pointoh Retrieved September 2, 2011, 2011, from https://journey24pointoh.com/2011/08/15/immigration-lack-of-debate/

Rusciano, F. L. (2008). The 2000 Presidential Election in Black and White. In R. Fiske-Rusciano (Ed.), Experiencing race, class, and gender in the United States (5th ed., pp. 175-179). Boston, Mass.: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance : an intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression (Vol. x, 403 p.). Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

The Pioneer Fund. (2011). The Founders Retrieved August 10, 2011, from http://www.pioneerfund.org/Founders.html

Tocqueville, A. d., Reeve, H., & Spencer, J. C. (1839). Democracy in America (3rd American ed.). New York: G. Adlard.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2009). Table HINC-05. Percent Distribution of Households, by Selected Characteristics Within Income Quintile and Top 5 Percent in 2009. In new05_000.htm (Ed.). Washington DC: U.S Census Bureau.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). 2010 National Population by Race. In c2010br-02.pdf (Ed.). Washington DC: U.S Census Bureau.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2011). Table 227. Educational Attainment by Selected Characteristics: 2009. In 11s0227.pdf (Ed.). Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

U.S. Commission On Civil Rights. (1980). Historical dimiscrimination in the immigration laws. In R. Fiske-Rusciano (Ed.), Experiencing race, class, and gender in the United States (5th ed.). Boston, Mass.: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

U.S. Congress, & Manning, J. (2011). Membership of the 112th Congress: A Profile. (0160537177). Washington: U.S. G.P.O. : For sale by the U.S. G.P.O., Supt. of Docs., Congressional Sales Office Retrieved from http://www.senate.gov/reference/resources/pdf/R41647.pdf.

U.S. Department of Justice, & Snell, T. (2010). Capital Punishment, 2009—Statistical Tables. In cp09st.pdf (Ed.). Washington DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

U.S. Department of Labor. (2011). Table A-2. Employment status of the civilian population by race, sex, and age. In empsit.t02.htm (Ed.), (pp. Economic News Release). Washington D.C.: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Zanna, M. P., & Olson, J. M. (1994). The psychology of prejudice. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Zeskind, L. (2005, October 23, 2005). The new nativism. The American Prospect Retrieved August 10, 2011, from http://prospect.org/cs/articles?articleId=10485

Zinn, H. (2003). A people’s history of the United States : 1492-present ([New ed.). New York: HarperCollins.

Zinn, H. (2010). The Twentieth Century : a people’s history. New York, NY: MJF Books.